"He Is Brave And Gentle And Wise..."

/

I don’t remember the old Astro Boy cartoon nearly as well as some of my friends do; like them, I first saw it when I was in elementary school, but all I’ve managed to retain is the super-lame theme song (“Strong-er than all the reeeest/This mighty ro-bot will pass the teeeest...” etc.), and the game at the end where Astro Boy summed up the plot but fibbed about an important detail to see if the viewers at home were paying attention. However, I know a lot of folks who swear by the show about the little boy ‘bot with the pointy hair, and who are devoted to the show’s emotionally wrenching storylines—like the one about the little girl robot who’s actually a bomb sent to destroy the show’s hero, but when she eventually falls in love with him, she runs off into the snow to explode alone. Thinking about it, that actually does sound kind of cool, but not as cool as the legendary two-parter The Greatest Robot On Earth, where an evil robot named Pluton begins tracking down and destroying the seven most advanced robots on the planet. When Astro Boy comes up in conversation, which is more often than you’d imagine, this is the storyline that is usually touted as his greatest adventure.

Apparently, legendary manga creator Naoki Urasawa (Monster) thought so too, even if his memories of Astro Boy were formed more by Osamu Tezuka’s original Tetsuwan Atom comics. Urasawa, overseen by Tezuka’s son, has taken it upon himself to create a retelling of The Greatest Robot On Earth with his manga series Pluto. Originally published in Japan in 2003, Pluto is now being imported to North America by Viz in a seven (I think) volume series. The first two volumes are available now, with more being released bi-monthly. As specific an homage as this series is, you don’t need to be a manga fan or an Astro Boy fan to appreciate what Urasawa’s done here. Pluto will appeal to fans of thoughtful science fiction in the vein of Asimov or Blade Runner, and is an early candidate for my favourite new series of the year.

Reformatting The Greatest Robot On Earth as a sort of police procedural thriller, Pluto follows a detective named Gesicht as he attempts to solve two possibly intertwined murder mysteries—the destruction of a series of highly advanced robots all over the world, and the gruesome slaying of various humans who are staunch advocates of human rights. The robots are all veterans of the 39th Central Asian War, and the human victims all belonged to a controversial survey group who were tasked with finding robotic weapons of mass destruction in a fictional country some years ago. Gesicht is aided by the Hannibal Lecter-like advice of Brau 1589, an incarcerated robot who is the only artificial being to ever murder a human (until now, possibly?), and a small robotic boy named Atom (he’s the one with the annoying theme song).

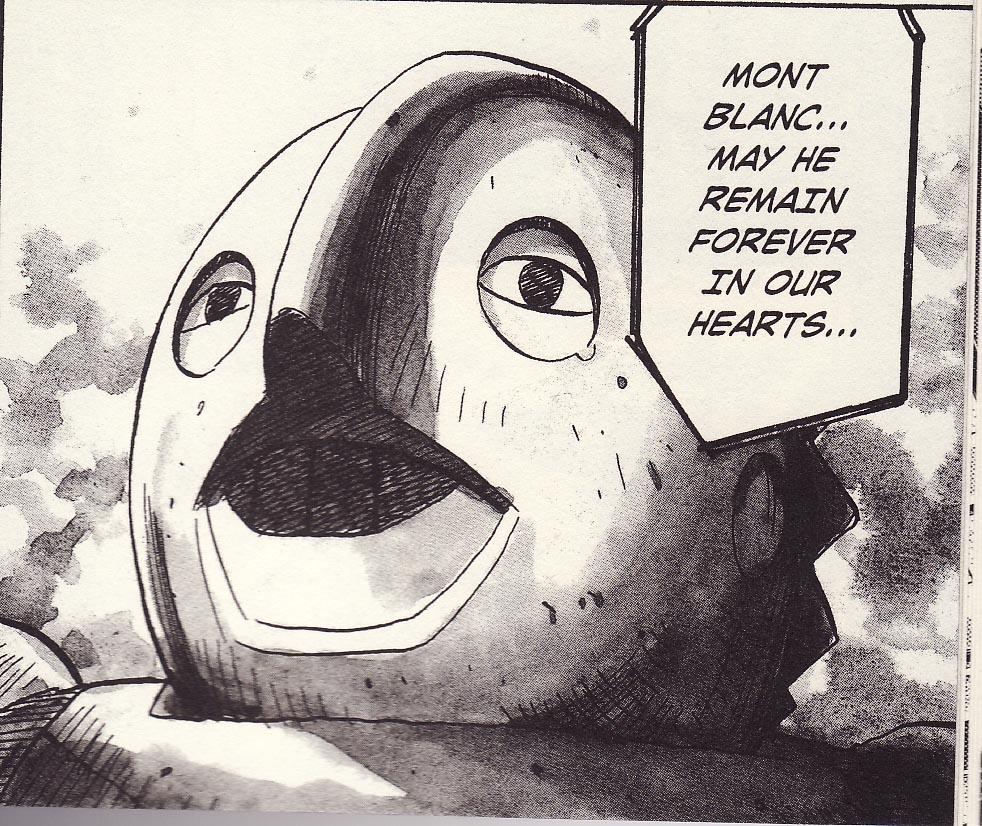

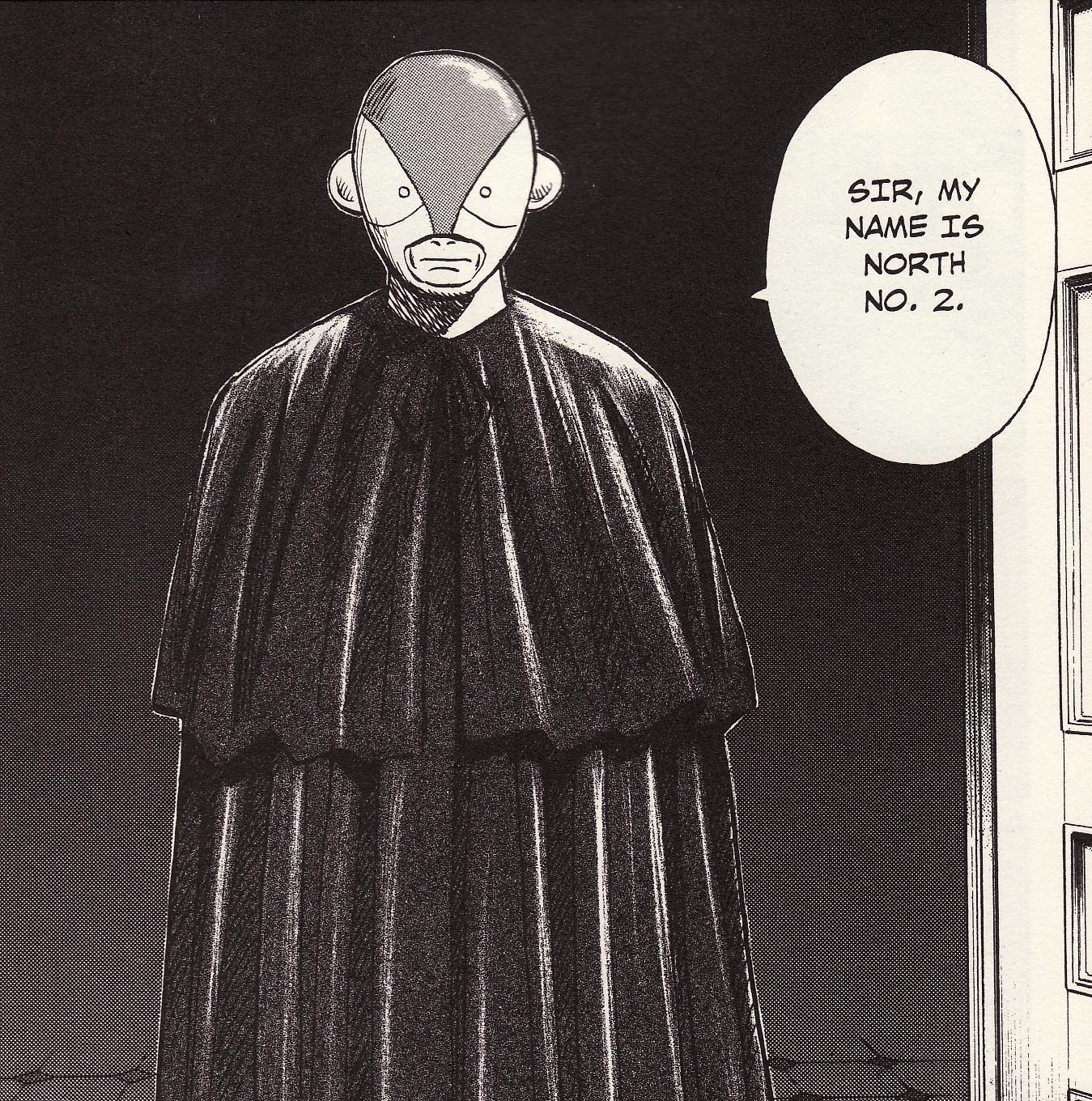

Set in a future world where humans and robots co-exist more or less peacefully, Pluto asks questions about life and emotions, artificial or otherwise. The robot victims are long past the search for humanity or emotion—they are more concerned with finding meaning and beauty in the world after surviving a terrible war where they were forced to do battle with their own kind. The doomed robots make for an intriguing cast of protagonists. There’s Mont Blanc, the mascot of the Swiss Forestry Service who is beloved across the globe; North No. 2, a serene would-be musician whose cloak conceals an array of deadly weaponry; and Brando, a literal rock ‘em-sock ‘em robot who, when not fighting in title bouts against other robots, is a family man with five rambunctious kids.

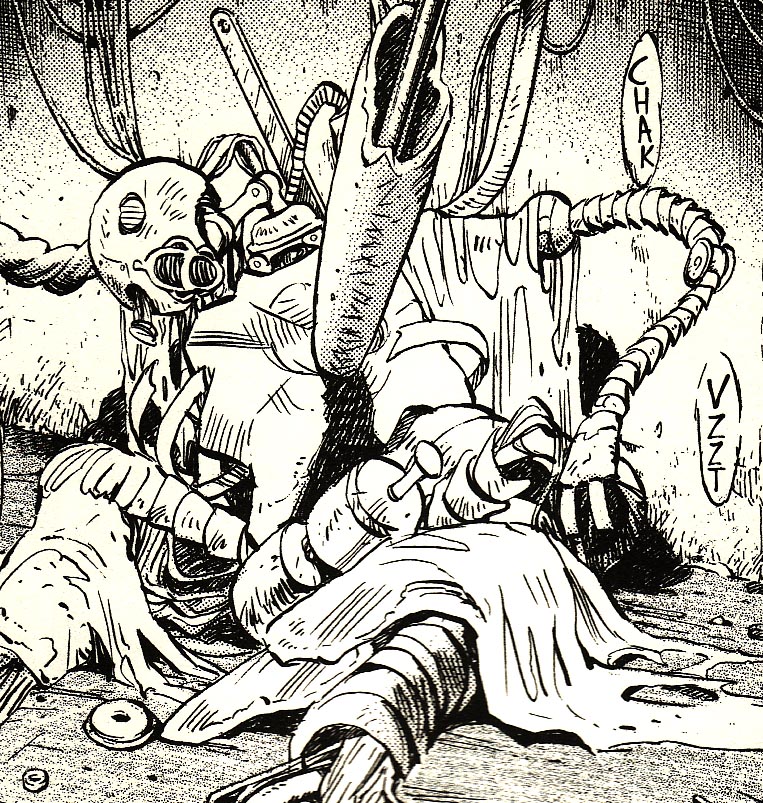

You’d have to be a robot yourself not to be caught up in the emotional component of Pluto. The global heartbreak and mourning that follows Mont Blanc’s destruction is weirdly affecting, as is Gesicht’s visit to the robotic widow of a police robot who is destroyed by a drug-addicted fugitive (and whose memory chip might provide a vital clue in the larger mystery). The centerpiece of the first volume is the three chapters devoted to North No. 2 and his new job as servant to a reclusive, sightless musical genius. The tumultuous relationship between the two is eventually healed as North No. 2 helps his master remember a song from his childhood that reveals a long-buried truth about his mother. The musician’s eventual acceptance of North No. 2 as a friend and collaborator makes the appearance of the mystery assailant pretty devastating, as do the scenes with Brando and his loving family.

That’s not to say that Pluto is simply a sci-fi hanky fest, though. There are plenty of other elements in the first two volumes to hold one’s interest—the intricate mystery behind both the robot and human murders is plenty involving, and the action scenes (like Gesicht’s foot pursuit of the drug-addled suspect in Volume 1, or Brando’s furious brawl with the killer in Volume 2) are fast-paced and exciting, and the interrogation scenes with Brau 1589 are ominously creepy. Urasawa’s art balances detail, action, and emotion nicely, finding depths of feeling even in North No. 2’s ever-unchanging expression and the blank face of the robot widow. Part sci-fi whodunit, part modern recontextualization of a classic adventure, Pluto is an exciting and essential new series. Just pay close attention to the details—there may be an untrustworthy recap at the end.